The Walking Simulators I Have Played and Loved

Although the term “walking simulator” is mostly used in a derogatory way to define games that focus on exploration, and do not have action elements or a clear opponent/enemy[1], it’s also something that has stuck as an umbrella term for the genre.

It is hard to exactly define the genre because most of the games are very distinctive among each other. In an another world, they might have been called “adventure games” but in our world that means puzzles and pointing and clicking that many of these games lack. In short, these games lack systems whereas games like Far Cry 4 are nothing but systems and their interactions. In this regard “walking sims” resemble interactive storytelling but give the player full control of their own character.

In my opinion the adventure games never died, their mechanics just got integrated into other, more action-oriented games. A good example of this is how Telltale has been able to revitalize the genre in games like Tales from the Borderlands[2] and how game series like Assassin’s Creed and Batman: Arkham are called action/adventure games. I would expect (and hope) other games to learn from “walking simulators” on how to deliver a story and do exploration that is not just collecting things.

“Walking sims” do share a lot with the old adventure games in the sense that it is the player who sets the pacing, there is very little the player has to react to by reflexes and the focus is on the narration. This is why I would argue that these exploration games are a natural evolution of adventure games where many new adventure games just try (and fail) turn back the clock[3].

This lack of systems and an adversary (or even a clear goal) make some people refuse to call “walking simulators” games, which - while technically correct[4] - fails completely to see how video games can achieve what movies and books cannot. Movies and books give the reader/watcher safety as they are mere observers and all the stuff happens to the characters - in video games you are often the main character. This is most powerful in horror games[5], and might explain why many walking simulators also borrow elements from horror stories.

Another thing that is common for these games that they have a lot of one-off stuff (like movies), which isn’t very common in more “normal” games. In your average FPS game you will eventually mow down same enemy type for uncountable times, these games often use locations and models only once.

Many of the games in this genre also choose not to use “realistic” art style and instead use stronger style, which is usually simpler and more distinct. Some games take this to the other extreme, like The Vanishing of Ethan Carter, and try to be very photo-realistic. Another commonality is that the games’ stories handle more mature, serious themes like alcoholism, death and sexuality.

One challenge these games face is that being very narrative driven they usually offer 2 - 5 hours of gameplay instead of the tens of hours that many people expect usually from video games. However, in my experience these games leave a much longer lasting effect.

Dear Esther (2008, 2012)

The entry point to the genre. The lineage no doubt goes further back than 2008, but Dear Esther set the trend for many games. Offering players little interaction and not being explicit on the story made many players frustrated but showed the others how video games can tell stories through the game itself and not just by having a talking head.

However, by leaving the story vague, the game also paved way for many cheap imitations that just tried to be artsy and deep but being just really pretentious. This game probably also started many threads on the internet about how games can be Art.

The creators, The Chinese Room, followed up with Everyobody’s Gone to the Rapture.

Journey (2012)

Many of these games come from developers who are interested in the more unconventional games or are games that started as research projects. Journey was developed by thatgamecompany whose previous games were flOw and Flower.

Other games in this list happen in a close representation of the real world, but Journey is a cartoony fantasy. This allows the game to express itself, its ideas and moods through the colors, shapes and other effects on the world itself.

Although Journey could be called a platformer game, the game does not have a scoring system nor really a fail state. Another distinct feature is that this game has multiplayer features. The other games rarely feature even any non-player characters in their game world. Also, the only game on the list that is only available on consoles.

The soundtrack of the game is simply amazing.

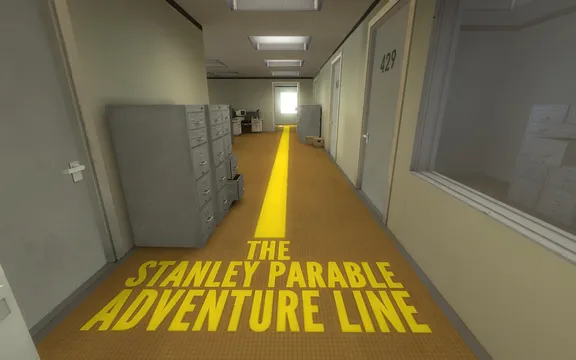

The Stanley Parable (2011, 2013)

The Stanley Parable differs from other games on the list in the sense that it tries to subvert video games and plays on the clichés and things players take for granted. It tries to deconstruct video games and lays bare the systems and illusions to the player that usually the player accepts unconsciously in other games. For example how in the end the player cannot have free will in a video game because the designer has had to define all the options and outcomes beforehand, and the game world, not bound by any laws of physics or reality, does not have to be coherent nor does the rule of a cause and a effect necessarily apply.

Obviously some of these apply to the real world as well, so the game experience can be a revelation to players not familiar with philosophy[6]. In that sense this game is the video game equivalent of The Matrix.

Like Dear Esther, the original version is a free mod built on Source SDK. I have not played the follow up game from the same creator, The Beginner’s Guide, which tells the story of a person struggling to deal with something they do not understand

. It’s rather common from story-related reasons that these games rarely have direct sequels but “spiritual” successors. If the game depends on a trick or a twist, it’s a very vain hope that people are amazed by it the second time[7].

Gone Home (2013)

Gone Home is a great example on how the focus and level of detail differs from more action oriented games. Even in a more exploration heavy game like Bioshock Infinite most of the buildings interiors would be just textures but in Gone Home most of the objects can be picked up and examined. The environments have to be very detailed in games like Gone Home or Firewatch because they play such a big role in them. In most games, if a mug can picked up, it has a function that serves the end goal of the game, but in these games it’s just a mug. However, being able to pick up any mug is important to the coherence and relatedness of the world.

The yet unreleased follow-up to Gone Home from (The) Fullbright (Company) will be Tacoma however in some ways Firewatch can be also seen as a successor to this game.

The Vanishing of Ethan Carter (2014)

The photo-realistic approach of Ethan Carter is in a stark contrast to Gone Home. This game happens in a small village and its surroundings and like Gone Home manages to hide a lot of hints in a world that looks entirely normal. However, this is also a bit of a weakness in this case as many friends have blissfully walked past many of the game’s puzzles not realizing they were supposed to do something and got stuck. Many other games manage to use the environment as a part of the story or as a way to tell the story, but here while breathtaking it’s just a backdrop.

Ethan Carter and its paranormal themes might have benefitted from a more expressionist art style (like Firewatch) although the contrast between the empty and calm-looking countryside with the game’s story is quite powerful.

Sunset (2015)

Unlike other games here, Sunset is a role-playing game but without any numbers. The game relies on the point that the player accepts the idea of the role the game puts them in. Also, Sunset does not explore space as much as it explores time. In most games the environment is very static, as if the player was stuck in a moment. Here the space is quite constant, you’re always cleaning the same apartment but time has progressed. What Sunset removes from the player is clear cause and effect, the player does not get immediate feedback on their actions nor can the player be even sure if the choice mattered.

The bigger story seems to be on its own trajectory and the game denies the player any part in it, forcing the player to be almost just an observer. Most games exist because they give a player a power fantasy (you are Batman!

), this game tries to make the player powerless. The player, after all, is just a foreign maid cleaning an apartment every week. It’s the other non-player characters who are fighting in the civil war.

Firewatch (2016)

As the latest entry to the genre, it’s clear Firewatch has benefitted a lot from all the games before it.

Like Sunset, the player is given a clear purpose and goals, you’re a lookout in a national forest and you get assignments from your boss. Like Gone Home, there are a lot of objects that are just doing their real-world thing, being. And, like Team Fortress 2, the games has hats (well, at least a hat) and a similar art style which like Journey is used expressively. And like The Stanley Parable, can you actually trust the game?

As anyone who has used the game’s unlikely publisher’s, Panic Inc.'s, Mac software[8] would guess, the attention to detail is on the same level. Firewatch sets the new level of storytelling and shows how video games can compete against TV series and movies.

The interactive medium gives these games an advantage how to reach their audience and make them feel and think. These games show how misguided some games’ attempt to be more “cinematic” is, if that is used as a way to tell a story. I’m all for stealing cues from cinema to entertain - comedy is especially hard in games.

While the game spends most of its time in outdoors like Ethan Carter, it makes sure that the player is never lost unless they want to.

The Witness (2016)

Technically not a walking simulator, as The Witness is closer to Myst, Portal and other puzzle games. However, it’s art style, audio and how the player moves around the game are very close to the other games on the list.

The game is the successor of Braid and every detail shows that Jonathan Blow has worked on it for 7 years, coincidentally when the first “walk simulators” were released. Unlike the other games listed here, the author is very clearly visible here[9] - just like you can tell a certain directors movies from others. Like The Vanishing of Ethan Carter and unlike Firewatch, Blow expects the players to figure things out for themselves. Even more like in Firewatch or Sunset, the world is purposely created for just this game. Like The Stanley Parable shows, Blow uses his power as the game designer to guide the player to see the game he wants even if the player thinks he has the choice.

And like “real” games, The Witness’ playtime is counted in tens of hours…

Notable mentions I have not (yet) played

There are many other games that have gotten a very positive reception but which I have not played. In no particular order,

- Everybody’s Gone to the Rapture

- Tacoma

- Mind: Path to Thalamus

- Ether One

- Proteus

- The Beginner’s Guide

I hope to remember to update this article if/when I play more games from this genre.

Although these days the term is also used for action games where a lot of player’s time is spent on walking around in the environment, like in ARMA. It could therefore be said that the use of the term tells more about the players’ patience than the games themselves. ↩︎

Or how Dontnod was able to beat Telltale in their own game with Life is Strange. ↩︎

f.e. Broken Age and Deponia. ↩︎

also known as the best way of correct. ↩︎

c.f. Amnesia series. ↩︎

For a more modern example, see The Talos Principle which is an excellent puzzle game but the story was a bit too pretentious. ↩︎

which is why it’s great they never did any sequels to The Matrix. ↩︎

However, many of the games were first games for their developers so they could’t even have a certain set voice. ↩︎