Destiny: Rise of Games as a Service

Now that the probably last paid expansion to Destiny, the Rise of Iron, is out before a probable full sequel coming out next year, I’d like to talk about my favorite topic, Games as a Service.

What does “service” mean for games?

As I’ve previously written on this blog[1], in my opinion one of the bigger, invisible, changes in the game industry has been the move from products to services. I’m not talking just about free to play[2] or microtransactions, which are just possibilities in a service model. This shift has been most visible on mobile games where hardly any game today is solely a product. On PC, all the most played games on Steam are all services[3]. Traditionally services have been defined by four facets[4]:

- Intangible - There is no box.

- Perishable - After 1,000 hours of Dota 2, you have very little physical to show for it.

- Inseparable - A service is always provided by someone and to someone, and does not exist without this connection (to server).

- Variable - No two experiences are the same.

These four aspects have at times been difficult to the players as paying customers to accept - I mean, it’s not like they asked for this shift. Many question what happens to their digital (intangible) games if Steam goes down (the games are inseparable from Steam). Some were hard against Microsoft’s plan to kill physical games and so the second-hand market (making games perishable). All of a sudden players are talking about netcode like it’s an everyday thing, which it kind of is as the (variable) quality of a game’s networking directly affects the quality of the experience. Also, in a multiplayer game, like the rating agencies always remind players, the interactions between players can vary a lot.

To back up a little, what does “service” actually mean in the context of games? Traditionally it has been synonymous with “online”; multiplayer, leaderboards and other features that require an internet connection to game servers. After EA's and Microsoft’s failures in use of the term “always online”, developers are not as eager to push “the cloud” as heavily as on other industries. “The cloud” usually refers just to backing up ones progress to a central server. “Always online” shouldn’t mean a failed attempt at copy protection or that the servers are down yet again, it should mean that players can play the game whenever, wherever.

I have summarised Games as a Service for games in my talks as

An offering to the player where he can engage with the game at any time and have new experiences.

or, for the managers as

Leveraging the interactive medium of video games with long-term retention, and managing the customer relationship lifecycle while focusing on the lifetime value of this relationship.

Destiny as a Service

So, how about consoles? When the current-gen was still “next-gen”, both Microsoft and Sony were pushing the cloud and free-to-play on the new consoles. Three years in to the current console cycle and I don’t think many games have had success similar to what has been seen on PC or mobile phones. I would argue this is because the market just isn’t ready for it yet.

One case example of the difficulties of bringing service-based games to consoles is Destiny, now at its year three of live operations. Although Destiny is still far from the “service-ness” of the “best of breed” games on other platforms, I think it’s one of the better attempts on the consoles in bringing AAA to GaaS.

The product offering for Destiny is very traditional, the base game is priced like any other AAA title, and at launch it had a run-of-the-mill “season pass” that collected the two first expansions. The two expansions added some storyline and unlocked some multiplayer content, just like Call of Duty's multiple DLCs do. So far, very product-like.

After played had consumed this content within the first six months, they were left wondering what else there is to do now - except insane grinding. The mistake Destiny made, I believe, was the one that most mobile and PC developers by now know to avoid - the content treadmill. No matter how much content Bungie would be able to deliver, the players would churn through it faster than they could deliver - and this gets expensive. The trick is to use the game’s systems to generate content/experiences for the players, preferably automatically and for ever. The traditional feature that fulfills these conditions is multiplayer. Destiny's problem here is that on this front it would be directly competing with Call of Duty[5].

My educated guess is that Bungie decided and locked the roadmap for Year 1 before launch and had no possibilities to actually react to how players play the game. Fortunately for the players, they figured their strengths for Year 2 in The Taken King. It was probably a hard sell for players as Bungie was essentially asking players to pay half the price of a full game for way less. On pure content terms this was true, the storyline was way shorter in The Taken King but where I think they succeeded was in utilizing their toolbox, their systems, in the ways the first two expansions failed. In addition, they were able to bring more live events to the game, most notably the “Sparrow Racing League” event that turned the shooter game into a racing game for a while.

Year 2 also saw the introduction of microtransactions in the shape of cosmetic loot boxes and “record books” that added more meta game to the game’s live events[6]. True, the end game was still mostly grinding, but what else can be expected from a game that borrowed heavily from RPG and MMO genres.

I would guess they had easier time for Rise of Iron, even though this expansion was yet lighter on single-player storyline content. I would imagine that the players knew that for the entry price they weren’t really paying for the expansions content as much as they were paying an annual fee to play Destiny.

There are many games that would love to be able to have a subscription model like World of Warcraft still does, but the market is so competitive that I don’t believe this is possible especially on consoles. The $13 per month WoW gets is obviously better than the $30 per year Destiny gets, and in theory allows Blizzard to deliver more content[7]. More traditionally, the season passes have been used to offer more experiences to the more engaged players but still keeping the entry price for more “casual” players. On PC, both Call of Duty and Rainbow Six: Siege have experimented with lower-price “starter” editions to increase their user base as these game’s life blood is the multiplayer and they can’t deliver it without other players to play against.

Free to play games have obviously brought the entry fee down to zero, but they have to better (or more aggressive) in finding revenue streams from the more engaged players. It is very unlikely that free to play will be the dominant business model for console games in the near future[8] because the number of games released is still low compared to PC or mobiles and the console players are more willing to pay an entry price for their experiences. However, the days when you bought a game from the self and paid one time fee for everything is long past.

However, this is not because game developers are just greedy, it’s because there exists a large percentage of players who are very engaged and want more. And this is where games can deliver, and books and movies have to resort to sequels. Thanks to digital delivery, which is the cornerstone that games can themselves be services, it is possible to deliver more. It’s not that developers try to nickel and dime and slice a “complete” game into chunks that the players “need” to pay separately for, it’s that they can deliver more. Previously, players would have paid $60 for Destiny, played it for a month, and left it there and waited few years for a sequel for their next hit of the world. Now they can play in that game for three years[9].

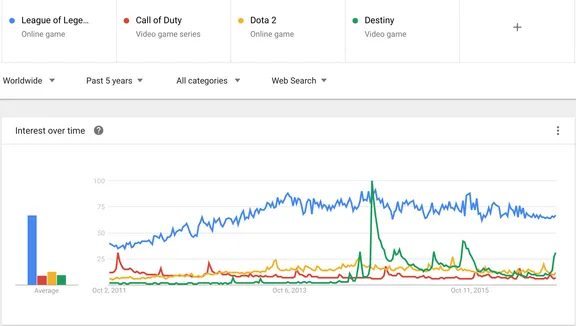

The ability to retain players for a longer time through the service model is what has made Dota 2 the beast it is. My favorite illustration of this is the Google Trends for various game franchises.

The interest for Call of Duty and Destiny only spike when a new game (or an expansion) is released, yet even these are dwarfed by the interest in League of Legends and its interest is much more stable over time. The graph gets more interesting when each entry to the Call of Duty series is separately. This just shows the power of systems over content and the power of long-term engagement.

I just hope Destiny 2 can deliver on day one.

Destiny is of course not the only game that has suffered these growing pains in the service world, another example is Ubisoft’s The Division, which too stumbled with its live operations and has since launch trying to learn how to actually do this whole thing. The Division seemed to have higher RPG and MMO aspirations than Destiny but its innovative PVP did not deliver to player’s high expectations - Destiny, on the other hand, relied more on the tried-and-true COD-style multiplayer modes and WOW-inspired PVE raids.

Meanwhile, Minecraft just keeps on going and expanding to further platforms allowing players to play whenever, wherever. Sure, the experience is not always the same “full” experience one gets on PC, but it is still Minecraft.

I previously wrote a little bit about Games as a Service in 2013 from which I also stole the title of this post as it fits with the Year 3 of Destiny. ↩︎

I liken the pricing model of F2P more to the shareware model of long past. ↩︎

Looking at Steam & Games Stats the only non-multiplayer games on top of the list are Football Manager 2016 and Fallout 4. ↩︎

and , Marketing Management, ↩︎

Call of Duty, like Battlefield, is mostly multiplayer games and the single-player campaign is - although insane in production values - mostly a one-time thing, a tutorial to the “real” multiplayer. ↩︎

The record books are somewhat similar to “Operations” in Counter-Strike: Global Offensive. ↩︎

However, as luring as the content treadmill sounds, it’s best avoided. For games as a service, the key thing is creating systems that keep the gameplay fresh and allow players to come in anytime and have a fun experience. ↩︎

It’s making forecasts like this that easily bite you later on… ↩︎

I guess it’s still possible to play Destiny online with just the base game bought three years ago… ↩︎