Power of Platforms

We are soon approaching the launch of the next generation of video game consoles, a generation that very well might be the last one, as predicted among others by Ubisoft’s Yves Guillemot[1]. This development is separate than the games as a service model, although both have their roots in general availability of high-speed broadband and mobile networks. There’s some overlap, both Sony and Microsoft advertise backwards compatibility on their next-gen[2] and how the successful multiplayer games you play today are available also on the next gen. This an example of how the platform is today more important than the device: neither Microsoft or Sony want you to “switch” to the other platform, which would the only way for you to “lose” your games library.

Guillemot talks about how streaming is the future - and it very well might be - but there is another way the concept of a game console “generation” is dead. Already by mid-cycle of the current generation, both Sony and Microsoft introduced more powerful versions of their consoles: The PS4 Pro and Xbox One X[3]. This idea of a single box seems to be dead with Microsoft branding their next-gen consoles as Xbox Series X[4] and Sony announcing a discless version[5] before launch[6]. Both are likely to announce “Pro” models later.

It will therefore be quite likely that the idea of a single generational device is dead. It will be interesting to see how both customers and developers react to this variety of device capabilities[7]. For the more casual players, who are used to just buying a box to play their games, this can cause confusion. For the enthusiasts, this can change the console device market closer to the PC, mobile and general home electronics market where hardware refreshes happen annually. It’s almost a paradox this happens now when the actual device starts to matter less and less. Curiously, this might make streaming platforms more desirable over the long term because they can guarantee “full” and stable performance at all times.

However, the one common theme on the console hardware front is that it’s a two-man race[8]. This is very unlikely to change. The entry costs are prohibitive, and challenging the duopoly seems to be very difficult even without a console[9] as Steam and Stadia have shown. Therefore, streaming is so important, not only for Sony and Microsoft but also for Google, Amazon and anyone else who wants to challenge the current state of video game console market. Sony, as the winner of the last generation, might be coming to the next-gen as a defender fighting the last war. Microsoft, on the other hand, is betting a lot on the Xbox “platform” which includes in addition to the consoles also Windows 10 PCs and the xCloud streaming service. Google is fighting an uphill battle with its Stadia service but has the war chest to fight for market share just like Microsoft had back in the early Xbox days. The evolution, or shift, from hardware boxes to the cloud opens the traditional video games market open for new entrants. Video games are the largest entertainment business in the world, so it would be insane for especially internet companies not to get in on the action.

It is therefore, in my opinion, wrong to say that companies like Amazon and Google are in the games for the wrong reasons; they are there for all the right reasons: money. The internet companies, especially those focusing on cloud services or those who otherwise have platforms, are in a prime position to challenge Sony and Microsoft. However, it’s a mistake to think that Google and Amazon[10] are into games just because they offer cloud services (to, among others, developers who make service-based games and so need servers and other internet infrastructure). This is not from where their competitive advantage comes from, cloud services are essentially commodities by now and a game developer can freely choose between any provider to build their game and where they distribute their game is independent of this choice. There will obviously be attempts to build vertical integrations, or vendor lock-in, so that it might be easier to use their services. However, these are unlikely to be related to streaming itself. For example, Amazon relicensed the Crysis engine as Lumberyard and built deep integrations for AWS. The game engine is free, and Amazon aims to make money out of the services the games use[11]. The name of the game is platforms, and by building vertical integrations they attempt to build a walled garden for both consumers and developers.

However, walled gardens can get anticompetitive quick. Apple is being investigated by the European Union because of their App Store rules. Epic, Facebook and others are challenging Apple to allow competing App Stores so that they could distribute and sell games[12] on iPhones and iPads without “giving” 30% of all sales to Apple[13]. It wouldn’t be fair to say competition wouldn’t be good; Epic was able to get some publishers to jump from Steam to Epic Games Store by promising more bang for their revenue share. However, this happened on one of thew open platforms (or, one could even argue, on Microsoft’s platform) and not on Steam’s platform. It is much harder to argue why Epic would be allowed to sell games on Steam without paying a dime to Valve. However, we are starting to see additional third-party services on top of these platforms. EA is offering their subscriptions services not only on Origin on PC, but also on PlayStation, Xbox and Steam. Ubisoft’s Uplay+ service should be available on Stadia this year. Conversly, PlayStation Now, xCloud and Stadia will be available on mobile platforms.

And it is really platforms on top of platforms and has been for a while. This goes to show the true power of owning a platform and why any big player not currently building one is way behind the curve.

Games on Facebook are a good example of how shifts in the device landscape can change the power structure radically. Before smartphones, everyone was building games for Facebook[14], especially after the early successes of games like Farmville. Because this was Facebook’s platform, they could take their cut of revenues generated. However, once the casual games started to shift to smartphones, this all changed. Instead of being on Facebook, games moved to app stores and although many casual games still took advantage of Facebook’s platform (ie. the social network), Facebook could not tap into the revenue stream. Facebook has later tried to bring games back, for example copying WeChat’s mini games feature to Messenger. However, due to Apple’s rules, they could not monetize on them on iOS. More recently, Facebook spun-off the games portal off Messenger to their own dedicated app, which is only available on Google Play for now. The shift from an open platform where Facebook had the walled garden to smartphones, where the hardware manufacturers owned the platform, totally changed how Facebook could extract value out of their platform. Similar challenges continue with Facebook’s more vital advertising business, where they can exert control of user tracking across the web but are increasingly prohibited of doing so on mobile by platform owners.

Another example of the power (or the lack of power) of platforms is Nvidia’s GeForce Now. Nvidia only sells hardware, or in this case, rent their hardware on the cloud, and doesn’t really have a platform and so doesn’t have any leverage on their service. On the contrary, publishers can dicatate which games players can play on GeForce Now - players that players have bought on other platforms. This raises interesting questions about who actually “owns” a game. From a player’s perspective this should be chilling, how can a publisher control how the game is played after a purchase. From a publisher’s point of view, it’s clear: they control on which platforms the games are available, Nvidia circumvents this and is a direct competitor to their potential platforms. This leaves Nvidia in a challenging place, even if they are partnering with Steam’s Cloud Play: in the future, they might be just one of the many streaming service Steam’s platform supports.

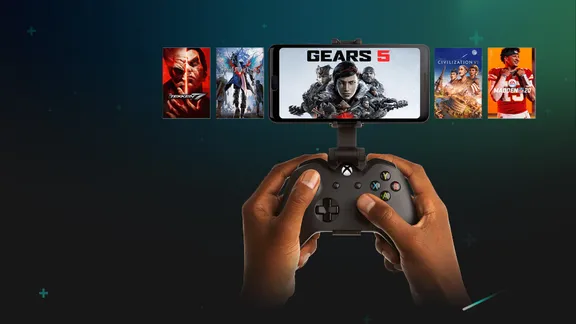

As mentioned before, the most interesting streaming challenger is Microsoft. They are pushing hard their platform and want to enable players to play games on “all” platforms. This makes things like Project xCloud a competitor to their own hardware and probably explains why they position xCloud as a complementary service. Tying it to the Xbox Game Pass and its library of games is however way less exciting than Stadia’s vision. However, as the example of GeForce Now showed, enabling xCloud for all games on Xbox would anyway require opt-in for publishers[15]. Right now, the much hyped transformative streaming future might fall on Stadia’s shoulders alone. It’s understandable that Microsoft would not want to cannibalize their existing business, but this means they are facing against the wrath of The Innovator’s Dilemma.

As a side note, I did not talk much about games that themselves are platforms - or aim to be platforms. The current GaaP stars, like Roblox (valued at $4 billion) and Fortnite (Epic Games valued at $18 billion), are attracting a lot of investments and VC money. The main reason for this, in my opinion, is that the investors see these games more as something like Facebook than a game, in other words it is the platform part that is interesting instead of the game part. As I noted in a previous post, one key success factor for GaaP titles is that they are platform-agnostic, which means that they are available across platforms and have been able to overcome the limitations of those platforms’ rules. Otherwise the investors would be better off investing in the companies providing the platform for Fortnite and Roblox, because they would still benefit from those games’ growth and of any others that might even surpass them one day. Only if these games manage to decouple themselves from the underlying platforms and build their own business of taking a cut do they start to become interesting for venture capital.

As Trip Hawkins once said, Either you have leverage and you monopolize and win, or you don’t have and you lose

. If you can’t get an exclusivity on sports franchises, your next best bet is platforms.

Although, he did also predict that 3D TVs would be a thing back in 2011. ↩︎

Microsoft going a bit further with their Smart Delivery feature. How many publishers will use this besides of Microsoft is an open question. Re-buying one’s media collection as a CD, DVD and/or a Blu-ray is a tried and true business in the entertainment industry. ↩︎

Before this, device manufacturers usually released “slim” versions of their consoles. These had the equal specs but due to the advances in hardware and manufacturing usually significantly smaller sizes and, hopefully, quieter fans. These were usually also cheaper and aimed towards more price-conscious market. The Xbox One X and PS4 Pro, on the other hand, were targeted as upgrades to enthusiasts. ↩︎

Microsoft however has a good track-record of infuriating developers with their changing hardware: Xbox 360 dropping the hard drive from its Arcade model (making it the opposite of a discless console) and on Xbox One announcing that every console definitely bundled Kinect and then dropping that soon after launch. ↩︎

I’m still waiting for an updated “Official PlayStation Used Game Instructional Video” for PlayStation 5 discless edition. ↩︎

Xbox One already had a digital-only edition, the One S. However, the previous PlayStations introduced the DVD (PS2) and Blu-ray (PS3) to the wider audience, the latter which settled the HD DVD and Blu-ray format war. ↩︎

Variable device performance has been normal for the PC games market, and I do not think neither players nor developers want that platform’s compatibility issues to consoles where things should just “work”. Mobile platforms seem to manage the insanely wide performance differences quite well, although mobile has very few if no AAA games that would be pushing the hardware to their limits. ↩︎

Nintendo, meanwhile, does their own thing. It’s good to note that almost half of Switch owners in the US have either a PlayStation or an Xbox. ↩︎

Let’s forget about the microconsoles like Ouya… ↩︎

It’s worth to note that there’s not much knowledge what Amazon plans to do on the gaming front. They do run Twitch (and recently offer its technology as an AWS service) and are developing games, although their track record is far from stellar. ↩︎

In contrast, Epic’s Unreal lives off a royalty but now provides a suite of online tools free for any engine (including Lumberyard). Epic’s game is different here, it aims to lure developers into using Epic’s account services and so build a larger player network that can challenge the social networks of Xbox, PSN, Steam and others. Maybe even Facebook? Unity has a more traditional approach where they “just” sell additional services. Apple, on the other hand, offers free cloud services for games using their iOS-only SDKs. Apple’s game is to have platform exclusive games in order to sell more devices. In my opinion, this is also why Apple’s Arcade service exists, it’s not to make directly money on games but to make their hardware more desirable to potential customers. ↩︎

Apple’s rules remain a challenge for both Google’s Stadia and Microsoft’s xCloud, but I would not be surprised the big players can make a deal with each other. ↩︎

In my opinion, it’s a bit dishonest to say that Apple is just a troll under the bridge taking a “toll”. There are a lot of things the platform owners provide on their platforms (not just Apple’s App Store, but also Valve’s Steam, Sony’s PlayStation, Microsoft’s Xbox, Google’s Play Store and Stadia and others) but it is a valid question if the universal 30% is fair. However, on Google’s Android, where other app stores are allowed, almost everyone still uses Google Play. Even Epic finally gave up and put Fortnite there. ↩︎

Notably, Facebook was similar to Steam that they both are a platform on top of an open platform. ↩︎

On Stadia, publishers opt-in by being on Stadia, which leaves xCloud in a bit of weird spot where it only works on some games. ↩︎