Skill Ratings and Matchmaking, Part 1

As multiplayer games grew in popularity, matchmaking - the backend machinery that decides who plays with whom - became far more noticeable. Back in the old days of lobbies, people more or less randomly piled together to play a game. However, people vary in skill and experience so wouldn’t it make sense to group people of equal skill to play together so that everyone can have a good time and not suffer (or enjoy) pubstomping? To do this, we need two things: first, a process to automatically matchmake people according to various attributes - like skill and latency - and second, a measure of a player’s skill.

In this series of posts, I’ll go through the history of matchmaking and skill ratings, and the practical implications of them on game design[1]. We’ll start with definitions and history of both matchmaking and skill ratings in games.

Matchmaking

Let’s start with a definition: matchmaking is the process of (automatically) grouping players so that they can play a match. Usually the designers aim to optimize the experience, in other words - but just as vaguely - maximize the fun.

The very rough history of matchmaking in games can be grouped by three seminal FPSs:

- Doom (1993), direct dial-up or IP connection

- Quake (1996), server browser (or lobbies)

- Halo 2 (2004), skill-based matchmaking (like TrueSkill)

It’s worth noticing that both Doom and Quake predate the mass adoption of always online broadband Internet. Before that, multiplayer games were usually played on LAN, so there was no need for automatic matchmaking. Once online became more available, games Quake would host a list of available (dedicated) servers players could connect to and once enough players had joined, the server would initiate a match. These servers would have some metadata to let players know what to expect (in terms of map rotation, game mode, player count or language used). However, this would still require quite a lot of work to find a suitable server and hope it wasn’t full or empty. Automatic matchmaking started to make sense once the player counts were high enough that the servers could be abstracted behind a simple “Play multiplayer” button[2].

As a sidenote on SBMM vs matchmaking. It’s entirely possible to do matchmaking and not use skill as a factor. Other attributes to use when matchmaking include: game mode, map, region, ping/latency, and player class. The SB in SBMM only indicates that skill is (likely) the main factor in the matchmaking, but still not necessarily the only component.

The introduction of automatic matchmaking hasn’t been without its critics, especially in games that had a

legacy of server browsers or lobbies. For example, Call of Duty had server browsers for a long time, until it recently introduced SBMM. This was not welcomed by the community, because among other things the players felt it made games more “difficult” because now all the players in a match had (ideally) similar skill levels. This robbed many higher skilled players from enjoying noob stomping. This is a legitimate grievance, although the noobs in this case probably had a much better experience. And not just probably, Call of Duty developers released studies on the effects of matchmaking and unsurprisingly found that players with a wider skill gap were more likely to quit matches in progress and did not return to the game at a higher rate

.

Many Battle Royale games also did not bother with skill-based matchmaking because it seemed luck played such a big role in a player’s placement (and this might have contributed to the success of the genre, anyone “can” win). However, these games have also introduced SBMM to some extent. Skill still matters, but the chaos and madness of these games adds so much variance that although in the long-term a more skilled player will place higher more consistently, there’s a higher variance of placement than in some other genres.

Although matchmaking is most familiar in competitive team-based games, matchmaking can also be done for co-op multiplayer game modes. Ghost Recon Wildlands, for example, matchmakes on players’ styles so that stealth players are matched with stealth players and not with all-out assault players.

This co-op example hints at a broader point: it shouldn’t be a surprise that matchmaking is not conceptually that different from content recommendation systems. The main difference is that in content recommendation systems there are two classes of “items”, users and content, and these are matched together[3]. Netflix and Spotify match users to media; games match users to users. Matchmaking in games just recommends users that go “well” together. Also, let’s not forget that notably Tinder used an Elo-based matchmaking system for a while. However, it is important to note that they do not do that anymore.

I quickly touched previously on that the goal of matchmaking is to optimize the experience. In practice this means that for competitive games, we usually want to make games feel “fair”. “Fair” can mean multiple things, but generally it means players are matched against players with similar skills. Ideally, each player has an equal chance (before the match) to win the match.

As mentioned before, this also means that the likelihood of blowout games is reduced so that fewer higher skilled players can enjoy dominating other players (although that will still happen) and also, each and every game can feel more “sweaty” as to have that equal win chance you need to play at your skill level and can’t just relax. We are touching here on some of the motivations people actually play games for, so from that point of view it is understandable that some might feel their experience actually suffer from automatic matchmaking.

Another implication of optimizing for “fair” games is that 50% win rate is the best a game can do even if game designers wanted to optimize for wins - because everyone wants to win! - as there logically has to always be both a winner and a loser.

One thing to keep in mind is that matchmaking refers to any way the game groups players together, it doesn’t need to be only by skill rating or even involve it at all. Another one is that while matchmaking attempts to create an ideal matchup, it is rarely possible to do so because of

- time limits (players don’t want to wait forever),

- population (top players will have less equal skilled players available)

- latency (the gameplay will suffer if the perfect opponent lives on the other side of the planet[4]), or

- other hard limits (like game mode or map, and to a lesser degree today, the platform)

and will often just satisfice and make up a “good enough” game. It’s all about trade-offs, and we’ll revisit these later on in the series.

Now, let’s move on to how games measure the skill that skill‑based matchmaking relies on.

Skill ratings

So, how does one measure a player’s skill rating? What does “skill” even mean?

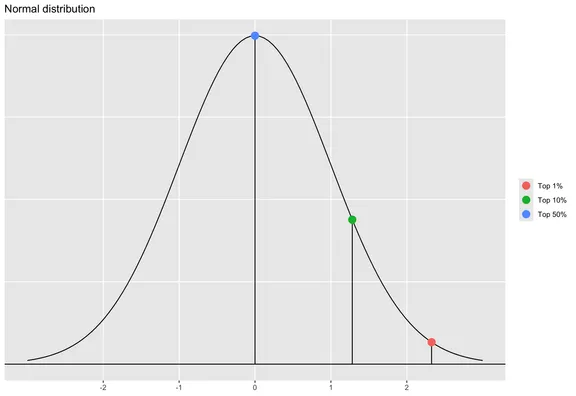

In general, we assume that players have an innate “skill” that is normally distributed and we attempt to estimate it based on their wins and losses[5]. This is not that big of a stretch; many human attributes seem to be roughly normally distributed, and we can also consider “skill” not just a single attribute but a combination of attributes and thus expect “skill” to be normally distributed[6].

The bigger problem is that humans (can) learn. However, we can assume that players learn at roughly a similar rate, so relatively this doesn’t change things too much. We can also assume that the true skill we are estimating is that long-term skill a player is capable of learning; the real skill level reveals itself through play as players learn the maps and weapons and other elements of the game.

In statistical terms, most systems assume that a player has a skill [7], but we do not know where on the curve that skill is. The best guess initially is that players are average, or . In other words, we assume a player has a skill value that comes from a normal distribution, and as we don’t initially know that value, we expect it to be the average.

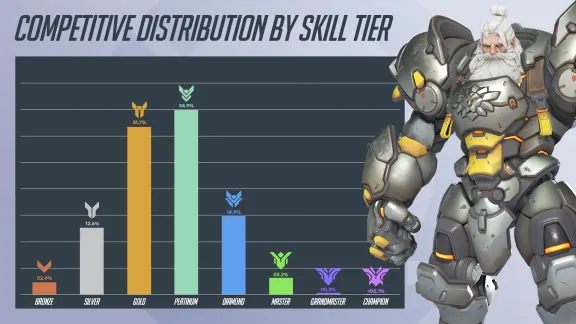

In the above figure, I have highlighted how far from average (Top 50%) the Top 10% and Top 1% are. A player’s skill rating needs to be one or two standard deviations larger to be in these groups. However, in practice, a game’s skill distribution is skewed much more to the right. For example, below is the skill distribution from Overwatch from mid-2025.

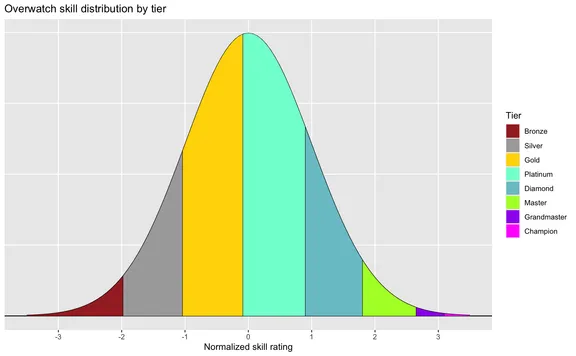

If we fit the above chart to a normal distribution[8], the tiers would look like below.

You will no doubt notice how symmetrical and close to standard deviations the tier limits are. This is not an accident, but very likely by design. Silver, Gold, Platinum and Diamond divide nicely ~95% of the skill curve[9].

It is worth noting that skill ratings work regardless how players are matched against each other. In fact, skill rating systems would benefit from uneven players matched against each other. This is because we learn more from unexpected results than from expected results. Players, however, will not appreciate uneven matches.

No matter how players are matched against each other, it is always possible to run a skill rating system in the background - or even afterwards from historical data - to rank players. A game can use skill ratings even if it doesn’t use it for match making, for example for leaderboards or content recommendations.

Why do skill ratings look at match outcomes and not at other features

You might be tempted to enrich the skill rating with some performance metrics from players, however, this isn’t without its drawbacks. First of all, it would open up the system for more abuse. Wins and losses are universal and unambiguous. Secondly, it can be argued it is the outcome that ultimately matters. Your K/D or accuracy doesn’t matter if you still lose. Thirdly, this was how Elo did it.

However, as mentioned, most systems measure “true” skill and the initial guess of average skill with high variance is very likely very wrong. This is why many systems in practice try to kickstart the process by initially measuring other factors to converge faster toward the player’s “true” skill level. For example, TrueSkill 2 - a SBMM system used on e.g. Halo 5 - kickstarts its skill ratings with player’s performance metrics. They are however only used in the beginning and afterwards only match outcomes matter.

How about the effect of poor teammates? If you always complain that you lose because of your teammates, note the only common thing in all of those matches is you. Learning to play with others is part of the game.

Popular skill rating systems

Elo basics

The best known (by name) is Elo rating system, created by Arpad Elo for chess tournaments. Wikipedia does a better job explaining the history of Elo, so I’ll just summarize it here.

Instead of arbitrary points, Elo created a statistical estimation where each player’s performance was assumed to follow the normal distribution, where the mean of that distribution is the player’s skill rating. A player who wins is assumed to have a higher rating than the one who loses, and so a player who won more games than expected would see their rating increase. The difference between a player’s rating compared to their opponent can be used to estimate how many games the player is expected to win. Elo’s model has a lot of assumptions that make the model simple to understand and to calculate, which probably explains why it remains the go-to when talking about skill ratings.

In the canonical example, we assume that the average rating of a player (Player A) is with a scale factor of 400 and K-factor [10]. If the player would be playing against Player B with , we could calculate the expected score with

In other words, we would expect player A to win the match with probability of 76%. The K-factor is then used to adjust the scores of the players. We denote Player A winning with (0 would mean a loss, and 0.5 a draw). The formula to update the rating is:

Conversely,

The win was expected so ratings aren’t updated that much. Had the match gone the other way around (there was after all a 1/4 chance for that), the adjustment would have been larger: .

One key insight into Elo is that we can rank players by their skill rating, where the higher ranked players have higher skill. The other thing, and more important from a matchmaking skill perspective, is that it is the difference between two skills that matters regardless what actual values of those two skills are. In other words, from matchmaking perspective, having a player with rating 1400 against a 1500 is the same as a 2400 playing against a 2300, both have a skill difference of |100|. Even more importantly, this difference can be transformed into a a priori probability of winning. A skill difference of 0 points is naturally 50-50, but for example we would expect a player with a +72 point difference to win 60% of time ().

What this means is that the matchmaking algorithm can set limits on how big the difference between skills can be, regardless what the actual skill levels are[11], for an even game. It will take longer to find players with a narrower skill difference so it’s trade-off between matchmaking time and whether 60-40 odds are within acceptable limits for your game.

Although other skill ratings differ in many ways from Elo’s system, they all have this nice property where we can use the skill ratings to get a probability and so observe how much our expected outcomes (from skill differences) match with observed outcomes. This lets us measure how good of a job our skill rating and matchmaking systems are doing[12].

How Elo’s assumptions break in online games

Elo is widely used[13], but it has many assumptions that do not hold that well for online video games. Among others,

- Chess is a perfect information game, so we can assume a player’s “strength” is purely skill (no luck, no better pieces, no map advantage, no classes…).

- Chess is a 1v1 game, so there are no teams or effects of them like team compositions or synergies.

- Matches are played in a tournament setting (rating period), in other words, players are playing at their peak performance over few days and are independent of each other.

The first point is not a big problem in practice with a broader definition of skill, because instead of “pure” skill we can attempt to capture just a player’s “strength”: we are not necessarily interested in measuring a player’s “true” skill. If they have better in-game weapons or equipment[14], or just a better mouse, we want to lump that in as well: we want to level the playing field no matter what the cause is. So, in general, when we talk about “skill”, we actually talk more generally about strength, of which skill is one (hopefully major) element.

We can solve the second problem by breaking down multiplayer games to pair-wise 1v1 matches. There are many ways to do this, just naively using transitivity (i.e. if and , then ) or using, for example, Simple Multiplayer Elo (SME) where we only consider the player having played two matches: a loss vs. the player right above him on the list, and a win vs. the player right below him.

The third problem is usually just hand-waved away, although I’d argue it’s an important departure from the assumptions: an online game is played continuously by ever-changing group of players and in various mental states and for various motivations. We can solve this issue somewhat by introducing uncertainty about the player’s skill, a feature of following systems.

One thing missing from Elo is how certain we are about our skill estimate. This shortcoming is addressed in the other systems mentioned, and it’s worth going into a bit deeper.

Modern systems: Glicko & TrueSkill

As mentioned, Elo system has its shortcomings. One major not mentioned is that it requires a lot of matches to converge close to a player’s “true” skill. In a tournament setting players have an equal number of matches (ratings) but this is not true for online games. Especially in the case of free-to-play games, the amount of games required to get reliable estimates is way beyond what we could expect an average player to play.

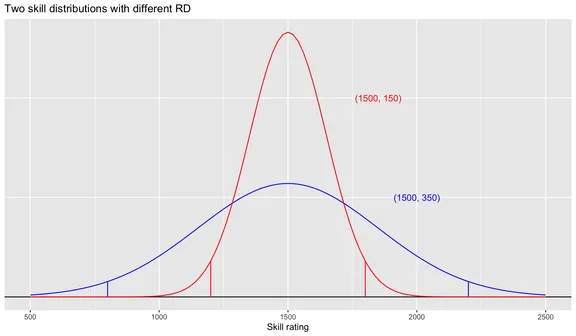

The other thing is that Elo does not consider the uncertainty of a player’s skill. As a simple example, in Elo there is no difference between a new player with an (assigned) estimate of 1500 against a seasoned player with an estimate of 1500. In reality, we are much more confident that 1500 is a good estimate for the seasoned player (ie. we are sure they are “average”) and we can be similarly quite confident that 1500 is not the “right” skill of a new player (they are just “new”). The Elo system would consider these two equal[15].

Glicko by Mark Glickman (or, more accurately Glicko-2, the improved iteration of the algorithm) is also designed for chess tournaments. It converges faster than Elo and uses a player-specific uncertainty parameter (RD) which allows for many nice things, like correctly measuring new and old players. The math is a bit more complex and longer than Elo system, so I won’t go into them here[16].

Glicko and other modern systems incorporate the element of uncertainty usually through a Bayesian approach to this problem. In short, a Bayesian approach does not think of a player’s skill as a single value but as a distribution with multiple parameters. Just how a player’s skill itself is an estimate on a (normal) distribution, so is our degree of uncertainty about that estimate.

In the above figure, we have two skill estimates where the rating estimate is 1500. Blue distribution has the Glicko-2 initial and red has a lower . Both distributions have lines indicating the 95% confidence intervals, in other words we are 95% confident that the player’s true skill estimate is between these two intervals. For blue this is 800-2200 and for red 1200-1800. In other words, we are quite confident blue’s skill estimate is at least 800 and red’s at least 1200. It’s likely red is the stronger player.

Microsoft’s TrueSkill expands further into the requirements of video games by handling more players than chess’s 1v1 and also natively supporting team games. However, it is possible to consider multiplayer team games in Elo or Glicko as pair-wise games. However, TrueSkill is designed with teams and online matches in mind. (Glicko-2, designed originally for chess, has also the chess tournament concept of a “rating period” which doesn’t make much sense for online games. In practice, this might not matter too much.)

TrueSkill (and its successor TrueSkill 2) is patented by Microsoft and cannot be used without a license in a commercial project. However, there are publicly available similar methods, one example is A Bayesian Approximation Method for Online Ranking by and (2011).

Role of uncertainty

The measure of uncertainty in Glicko and TrueSkill is quite useful. Some might consider uncertainty a disadvantage, but on the contrary systems that do not consider uncertainty only offer an illusion of certainty. In fact, being able to adjust the uncertainty of our skill estimate lets us handle many practical issues in online games including skill decay and season resets.

Online games are played 24/7 with players playing continuously instead of in a tournament as assumed by Elo. This means we cannot expect players to play at their peak performance. Quite the opposite, it could be easily argued that most games are played for entertainment and relaxation. It is therefore unrealistic to assume that a player will always play at their “expected” level of skill.

Few, if any, matchmaking systems account for player’s state of mind (alertness, sobriety) or intent (casual, try hard, trolling). A player who has had a few beers is probably not playing on their “normal” level so their match performance probably should not be weighted similarly to their normal play when estimating their “true” skill. However, if the game knows that a player is not playing “normally”, we could increase our uncertainty accordingly.

It is also a fair assumption that if a player hasn’t played in a while, their skill has probably “decayed”. Instead of adjusting their skill point estimate (because their “true” skill hasn’t probably changed, they just need to “warm-up” first), we can again just increase our uncertainty of their skill.

In Elo-rated tournaments, there is also the problem where high-rated players do not want to play at all because they can only lose their rating. Even if the expected win probability would be high (>90%), pure chance and other real-life factors can mean it is actually closer to 70% (in statistics this is known as fat tails). With skill decay and using a low confidence interval for player ranking (increasing uncertainty), players cannot hold on to their high rating by not playing.

Similarly, once the game’s rules or a season is changed, we can account for this by resetting (or, increasing) players’ uncertainties and leave the point estimates alone. This is what most games do when they do a reset, even though this might be communicated to the player visually as a skill point decrease[17].

In a Bayesian system, we always want to add information, not wipe our knowledge.

We have no reason to believe that changing a season or rules will decrease all players’ skill, but we have a reason to believe that our certainty of that skill has decreased. By increasing the uncertainty, we allow the estimates of players’ skills to vary more, so the new changes are incorporated faster into our estimates.

Conclusion

In this post, I’ve defined what matchmaking and skill ratings are and what they do. I also went a bit into detail of the role uncertainty about a skill rating, because it’s an additional number we can use in multiplayer game design. In the next post, I will go deeper into what implications these systems have for game design and experience and how skill ratings can be used outside of matchmaking.

I’ll add a link here to Part 2 once it’s published.

For other overviews on these topics, check Ranking and Matchmaking - How to rate players’ skills for fun and competitive gaming by Thore Graepel and Ralf Herbrich and Elo, MMR and Matchmaking -an in depth coverage! by /u/NMaresz. I would also recommend the following GDC presentations: Ranking Systems: Elo, TrueSkill and Your Own by Mario Izquierdo, and Skill, Matchmaking, and Ranking Systems Design, Matchmaking for Engagement: Lessons from Halo 5 and Machine Learning for Optimal Matchmaking all by Josh Menke. ↩︎

Team Fortress 2 is one rare example of an old enough game that started with a server browser and then later introduced gradually automatic match making, having an in-between step, where the game would auto-pick a server for the player. ↩︎

I haven’t introduced skill ratings yet, so this note is relegated to footnotes but nothing really stops from attempting to calculate a skill rating to a level in a single player game. We could theoretically measure players’ success (win) rate against levels and in that way calculate both skills of players and difficulties of levels difficulty automatically. Some Match-3 puzzle games on mobile very likely do something like this, and no doubt some puzzle games do this before general release to adjust the order of levels in the game. ↩︎

The speed of light is terribly slow even on just Earth. Theoretically it would take 70ms for light to reach the other side of the Earth, but in practice ping would be around 150-300ms. Quite unacceptable for an FPS. ↩︎

And ties, if those are possible and meaningful. ↩︎

See Central limit theorem. ↩︎

This is not exactly true, as a more suitable distribution would have fatter tails, because in practice extreme events are more likely than what normal distribution would allow. The distribution would also be skewed to the right because of populatiion churn and other factors. For simplicity, I’m using normal distribution here. ↩︎

Again, this is a conceptual simplification, empirical skill distributions are often right-skewed due to various factors. ↩︎

See Confidence interval. ↩︎

The selection of scale and K-factor here are the canonical values, which might not be the most optimal values for a game. They are used here so my examples match with Wikipedia and most other sources. ↩︎

Although, in practice it’s easier to find players with smaller difference closer to the mean of the skill rating distribution than at the tails. This means that better players will end up waiting longer for a closer matchup. ↩︎

And also see how well skill explains winning in our game, not necessarily a given! ↩︎

Quite often “Elo” (or even ELO) might be used as a short-hand for any skill rating system, or for a skill rating so you can’t always be sure what the actual used system is. Also, while many systems might be based from Elo, they might not be exactly like the canonical example on Wikipedia. ↩︎

If everyone moves to playing with stronger characters, classes or weapons, this balances itself out and the skill rating represents more the actual skill, but if the game elements have strong imbalance, it has effects on the actual experience when everyone is running a similar “meta” build. ↩︎

This is why some games have different pools for new players and others, so new players only play against other new players. This however has the drawback that it might make it even more jarring once a player is no longer considered a newbie and is matched against more experience, but equally skilled players. Especially games that have been around for longer will almost inevitably face this problem - especially when the pool of existing players is heavily biased towards higher skilled players and/or small. ↩︎

The Glicko-2 paper (PDF) is simple enough. You can additionally find my Python implementations of both Glicko-2 and Weng and Lin’s system on Github. ↩︎

I’ll go more in detail why this happens in a later post. ↩︎